Howard Skempton

Here’s an interview with Howard Skempton ahead of our concert with him on Thursday 26th. Ged Barry from the orchestra interviewed him and in the interview Howard talks about his musical influences, life in The Scratch Orchestra, and his views on experimental music and improvisation.

Howard Skempton interview. April 2018

The interview took place by phone.

GB. What were your early music experiences and training?

HS. I think I’m largely self taught. I was in a choir at school and I was always going over to The Bluecoat Arts centre in Liverpool. I was also always getting cheap tickets at The Liverpool Phil for their Industrial Concerts. They were once a month, so I heard all the standard works, and then I was encouraged when I was doing O’level to do composing. I’d tried before a bit and the music teacher said it was very good. So at that moment I made or my mind there and then, that composing is what I should do. But it’s partly because I wasn’t good at anything else. I was sort of rescued by composition. I then changed my piano teacher and he was interested in early music, but by then I was more interested in composing more than playing and I was definitely interested in Stockhausen and Cage. I gave the school library a book on Cage when I left, that infuriated some people.

GB. Too radical for them?

HS. I think so.

GB. Did you go to London after finishing school?

HS. No I had a gap year working in Liverpool doing voluntary work and then went down to London and studied with the composer Cornelius Cardew. So you can see it was rather a curious education. I had various music interviews to study music and I had a interview at RNCM, though I think I was too alarming for them because I was so passionate about new music. I was also cross that I couldn’t study composition. I remember I did a piano audition there, I played one of my pieces and a long piece by Morton Feldman and a Bach prelude. I was sort of testing the water. I don’t know whether it was arrogance, or whether it was uncertainty, whether or not I’d survive in a conventional world.

GB. What date was this?

HS. This is going right back to 1966 or 1967.

GB. So you were in Liverpool during The Beatles?

HS. Yes absolutely, my older brother was going off and seeing Bob Dylan and The Spinners at The Empire or the Royal Court, and the Beatles at the Cavern. I didn’t do that, I went to the Bluecoat and saw experimental work, and you would see people like the poet Adrian Henry hanging out. So the Liverpool poets were there as well. It was very much the Liverpool of that time, it was the centre of the world. So no wonder I was so competent, and I knew exactly what I wanted to do because I was interested in Stockhausen and Cage and knew I wanted to study with Cornelius Cardew.

GB. Did Cardew study with Cage and Stockhausen?

HS. No he worked with both of them.

GB. But he was closer to Cage wasn’t he?

HS. Yes he moved towards Cage. He looked west to the States, to Feldman and Cage, but also to Europe.

GB. Did you study music in a college in London?

HS. I was a student in London for 3 years doing a general degree.

GB. Was that at Morley college? I remember reading you did stuff there.

HS. Yes I did, but this degree was at Ealing technical college. I was there as a pretext to get to London to study with Cardew. Ealing was a lively place and previous students there had been Freddy Mercury and Pete Townsend. It was like an arts school and there were lots of talented people there. I went there and I was meeting people doing photography and art. I was doing a general degree but I’d chosen to do psychology, history of art and music, all of which I was interested in. So it wasn’t a typical course. I failed at the end because I was too busy working as a musician. I even had a concert the day before my music finals. Also because it was an external degree it was more or less unsatisfactory in many ways and I sort of dropped out.

GB. Did you do any experimental music there?

HS. The great thing about being at Ealing was I was able to organise things. I charged in there and within 3 or 4 weeks I’d put up some handwritten notices around the college. I hired the lecture theatre and I performed Cage’s Lecture On Nothing. With an audience of about 50 or 60. We did one of my pieces Drum No 1 and the Scratch Orchestra came there a couple of times. So there were some very interesting people teaching, it was more like an arts school, and you know some of Cardew’s friends like John Tilbury and Gavin Bryars were teaching in arts schools. Also from the art world was Brian Eno who was a member of the Scratch Orchestra. I worked with Brian a few years later, it’s a very particular world, and I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time.

GB. What did you do for money when you finished studying? As I can’t imagine there was a lot of money, like now, playing experimental music.

HS. Oh I needed a job desperately so I got a job in music publishing because I was interested in all sorts of music. I didn’t have a narrow interest. So publishing was good for me, meeting a wide range of composers.

GB. Which music publishers?

HS. Faber.

GB. Didn’t Cornelius Cardew work as a publisher as well?

HS. No, he worked as a graphic designer. He was such a good musician but mainly he didn’t want to be a working musician in a conventional way because he wanted to be free I guess. When I told him I’d got a job working in Faber he said, ‘Howard you’d be better off working in Boots’. So there you go, that was his view. But then he came around to Faber and had some tea and he very much appreciated that I fitted in. I was very happy working in Faber. I also started doing some freelance editing and I worked as Feldman’s editor for a few years. I met all the composers I admired. I even wrote a left hand piano piece for Benjamin Britten. And those are the piano pieces that John Tilbury has recorded. So most of my music from the time of the Scratch orchestra, and for about 20 years onwards was either piano music or pieces written for concerts with Michael Parsons, or one or two friends who hadn’t turned to politics. We were doing concerts in galleries, well all over the place, but on a very small scale. There are also a few clarinet pieces and percussion pieces that I performed with Michael Parsons. But the piano pieces kept on going. Also through publishing I met Michael Finnissy and he was very helpful.

GB. So you were composing a lot?

HS. Well I married in the mid 80s and we moved up to the midlands. I wrote a set of pieces called Images for a channel 4 series and then the BBC commissioned Lento. And then I started, when my son went to school, to get commissions. It was a very happy thing to happen. So some commissions came in, not a lot, but since the 90s I’ve been mainly working to commission and in the last 12 years to teaching.

GB. Where do you teach?

HS. At the conservatoire in Birmingham. So things are sort of spreading and growing all the time. But also keeping in touch with friends like John Tilbury. I went to stay at John’s just before Christmas, because he wants to record some of my pieces he hasn’t recorded yet. Also last year I went to Norway with John, Keith Rowe and Eddie Prevost from AMM for a Cardew weekend. So I’m still very much in touch with old friends. In fact on Friday I was in the Wigmore Hall for a Fred Rzewski 80th birthday concert, sitting behind me was Michael Chant from the Scratch Orchestra and in front Dave Smith, another old friend. It was very good to keep in touch. If experimental music means anything it’s a sort of family, it’s the tradition from which I came. So you ask about my education, well it’s experimental music and composers such as Cage, Feldman and Christian Wolff. Particular Feldman, then Cardew, and Stockhausen was important. I had a chance to study with Stockhausen but I ducked and studied with Cardew instead.

GB. Where you studying with Cardew privately?

HS. Before I went to London in the year after leaving school I got in touch with Cardew. I wrote to Stockhausen as well. But I arranged to study privately with Cardew. The first published piece I wrote,

I regard as my first is The Humming Song, it’s almost like a prototype for everything I’ve done afterwards, it was written before I studied with Cardew.

GB. Were the lessons one to one or a group class?

HS. Well I wrote to him and he said I don’t actually teach but we can have consultations, so these were one to one lessons. And he said you can come when you’ve got something to show me and I’ll charge you accordingly. And it was quite a lot of money, it was about £5, which in those days was a lot of money, about £60 now.

GB. For an hour?

HS. No, he was very generous and sometimes it stretched to an hour and a half. But given that I was paying £5 to take the train from Liverpool it was a lot of money. I’d saved up enough to pay for the lessons but I couldn’t afford to see him more than every 6 weeks. But I guess I saw him probably three times before I went to London. And then I saw him maybe 3 times when I was in London. But by then I was seeing him regularly because I was taking part in concerts.

GB. So he asked you to join the Scratch orchestra?

HS. It’s extraordinary, the first time I saw him in London he asked why I wasn’t taking part in his piece, The Tiger’s Mind, well I said, ‘I’d love to’, and so I took part in the first performance of that piece. And then he invited me to his class at the academy. So I sat in on a class though I wasn’t a student. It’s a bit like the artists Gilbert and George, apparently George was not a student, he just came along to the lectures and just sat there, sort of just gate crashed. So I was involved and I knew all of Cardew’s students because we were doing things together as well. So when School Time Compositions by Cardew was first performed, about after a few months after I arrived in London, I took part in that as well. And then in June, one of his students, Christopher Hobbs, organised a concert, and that’s when I took part in Play, by Christian Wolff, also in the 1st UK performance of In C by Terry Riley. So as you can see I was part of that circle and of course that circle included people like John Tilbury. Christian Wolff happened to be on sabbatical, he was teaching at Harvard I think, teaching Greek. He was in England and, as soon as I arrived in London, as I said, I went to see Cardew, and Cardew said go and see Christian. So Cardew arranged that I go and see Christian, and I reminder spending a couple of hours at Christian’s and I remember he didn’t charge me. That was extraordinary, because Christian was a great hero of mine. So Ged, you can imagine, I arrive in London, and go and see Cardew and he tells me to go and see Christian. So I go on a tube and go and see Christian, and then 2 hours with Christian. I mean everything seemed to be handed to me on a plate.

GB. Yeah it sounds like it.

HS. But this was after a whole year of frustration and not knowing what I was going to do after leaving school. So I had a gap year and I was working for Liverpool council in social service, but not getting paid properly because it was voluntary work. And really I was at a complete loss. But always knowing precisely what it was I wanted to do.

GB. Which was quite amazing considering how young you were at that time.

HS. Yes I suppose so. I remember when Cornelius asked me to become a founder member of the Scratch Orchestra. I was only earning what any other student had at the time but I managed to get by as I was very restrained and I had £5 in my pocket. So I became a co- founder of the Scratch Orchestra. I had £5, Michael parsons had £5 and Cornelius had £5 paid so we started the Scratch Orchestra together. So it was a simple as that. I think Cardew thought I was older than I was. I think I must have given the impression because I was a sort of Satiesque figure and I refused to look like a hippy, a bit like John White I just seemed a bit more self possessed, maybe? I knew what I wanted to do and I had sort of confidence coming from Liverpool as one does.

GB. As you said at that time it felt like the centre of the world.

HS. Yes it was, and I had so many contacts, as I said in my gap year I worked at The Bluecoat, it was Bill and Wendy Harper running it at that time.

GB. Bill Harper who still runs The Blackie arts centre?

HS. Yes he did that soon after the Bluecoat. The Blackie started about 1970 I think?

GB. Bill’s still the director of it as far as I know.

HS. My goodness he’s still going. Because I’m going back nearly 50 years now. So he’s still doing it?

GB. Yes I think he is.

Hs. Well he must be 80 by now?

GB. Not sure, but he’s certainly knocking on. He also commissioned the Pierre Henry composition for the opening of Liverpool’s metropolitan cathedral. It was also performed last year for their 50th anniversary.

HS. Yes, I know that piece because I was at the opening. This was my main interest in the mid 60s, electronic music, tape music. This is why it’s ironic that with Cardew, well he’d gone to study electronic music with Stockhausen, and as I said I was particularly interested in electronic music. But Cardew said, ‘no Howard the speakers aren’t good enough’. Also what Cardew didn’t like about the studio was the sort of ivory tower nature of it. For him music was everything except that, that’s one thing that was an anathema to Cardew, the ivory tower. And I think we all learnt that lesson from him. It’s ironic because I was visiting professor at De Montford university and they don’t do anything apart from electro acoustic work. The professor there said we want someone there from a different discipline, but he knew I was interested in electro acoustic work but Cardew had steered me away from it. Going back to Bill Harper, the first concert of the Pierre Henry piece, it wasn’t performed was it?

GB. Part of it was done at the opening from what I gather, some of it wasn’t finished in time.

HS. Oh yes now I remember. Unfortunately he’s just died hasn’t he?

GB. Yes the piece was performed in the cathedral and then he died shortly afterwards.

HS. Yes, he would have been about 90 by then I think.

GB. Yes he was 90. It was an amazing, incredible piece to hear it in the cathedral. I couldn’t believe that the Catholic Church had ever commissioned it.

HS. I’ve just recently bought an LP of electro acoustic music from that period and I love it, it’s so raw compared to electro acoustic music now. Because it’s using those real sounds. It’s raw material.

GB. The Pierre Henry piece certainly used a lot of real sounds. I’d like to ask what were the opportunities for a musician/composer involved in experimental music in the 60s and 70s.

HS. The thing is if you were adventurous at that time there was so little places to go, nowhere to go.

GB. This is interesting because it feels like that is the same now, maybe possibly even worse? How was it with the Scratch Orchestra and audiences?

HS. We had very small audiences. Usually there were more members in the orchestra than audience. Though it’s been incredibly influential, you know a lot of people will want to know about the Scratch Orchestra, mainly thanks to Cardew. He was the great imaginative centre of the whole thing. It was always exciting and a very happy time being a member, though sometimes frustrating as well. Brian Eno said the Scratch Orchestra was interesting because people seemed more interested in behaviour than music. It’s like an Alvin Lucier piece, it’s how people respond. It’s setting up a situation, like performing on a tube train, or doing an environmental piece and seeing how people react to it. Or trying things out. And of course what you develop is how things work, which is the best lesson.

GB. You’ve talked a lot about the Scratch Orchestra and I feel that the Merseyside Improvisers Orchestra is in some ways continuing the tradition of the Scratch Orchestra, or I certainly feel a kinship with it. Also John Tilbury is one of my heroes. He was actually the piano professor where I studied. Anyway The Merseyside Improvisers Orchestra have played text scores, graphic scores, free improvisations. Some of these pieces were written 50 years ago! It’s not exactly new. Sometimes playing in the orchestra I think at times audiences think we’re lunatics, I can’t imagine what they thought of the Scratch Orchestra as it was completely new and starting the tradition.

HS. Lunatics, ha, ha, yes, join the club. And yet with some of the pieces like Burdocks by Christian Wolff, they work beautifully, also The Great Learning by Cardew. There’s a real magic, and of course there is something really special when it works properly. I’ll bring one of my pieces for our concert, For Strings, and I’ll expect the magic to work.

GB. I’m sure it will. We’ll try our best.

HS. Actually that piece predates the Scratch Orchestra as well, it was written for Morley college. Well Cardew was impressed by it as well as Drum No1 and he and 3 other people, well, AMM, did a broadcast of it. I mean that’s fantastic. Being a young composer, I was still a student and I was in a BBC studio. They got quite a shock when I told them what the score was. I said it’s only some words.

GB. Could something like that happen now? Or was it the spirit of the 60s?

HS. I think it might, with things like Late Junction on Radio 3. They have a series called exposure and they go around the country and hear groups. I don’t know if they’ve done one from Liverpool? A Lot of this work is as very big as experimental I imagine as the Merseyside Improvisers Orchestra are doing. One thing I guess, or promise, is that you wouldn’t be as anarchic as the Scratch Orchestra! Cardew said at one time he regarded it as an oracle. It enabled him, it gave him food for thought, the Scratch Orchestra. It asked very serious questions. The great thing about studying with Cardew is that it has given me an interest in serious questions about music. Like the questions Cage was asking, what is music? I now go into the conservatoire and I ask the same questions. I’m known for asking these questions, I may not do anything else but I’ll ask these silly basic questions. And that’s what experimental music is doing. And that’s what you’re doing. The other thing Ged, is that’s it’s been described as a sort of urban folk music.

GB. That’s lovely.

HS. It’s not a bad phrase and it’s good to hang onto.

GB. A lot of your music is very melodic. Is melody very important to you?

HS. If I believe in anything, I believe in melody. Pitch is fabulous, to be able to focus on something as precise as that.

GB. What are your thoughts on improvisation?

HS. Well I love AMM. Improvisation, it’s all about listening and being really curious and surprised by what comes next. And having a real sense of exploration starting with nothing. It should have an energy and urgency, but one hopes it’s not going to be self indulgent. You shouldn’t make a sound unless you feel it contributes in some way. Cardew was devoted to improvisation and in the Scratch Orchestra, he said if you can’t hear an instrument you can see, stop playing.

GB. Very useful advice. Thanks for your time Howard.

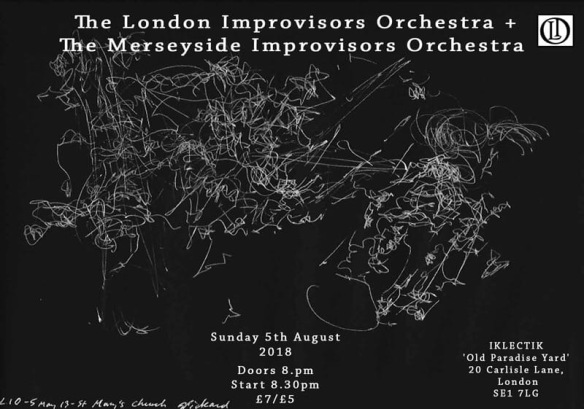

We’ve been invited to play with The London Improvisers Orchestra at Iklectik. Wonderful group of musicians, improvising Orchestras Of The world unite!

We’ve been invited to play with The London Improvisers Orchestra at Iklectik. Wonderful group of musicians, improvising Orchestras Of The world unite!